Books and cooking are perfect companions. I never tire of reading about food, about the preparation of it, the soul-nourishing properties of selecting and preparing what we eat, the way we dream and think about ingredients and countrysides and fields and markets and tables. Or the way we recall meals enjoyed in restaurants and gardens and backyards.

Cookbooks and volumes on wine and food and all things culinary occupy large amounts of space on the shelves of my bookcases, and I consult them often. (Or, I should say, will again once my books are out of boxes and back on said shelves.) Indeed, I miss terribly sitting with The French Laundry Cookbook and The Gift of Southern Cooking, among others, and delving into the passions of Edna Lewis and Thomas Keller. I miss my Le Guide Culinare. In the past several months I have found myself wishing I had easy access to On Food and Cooking and the words of Mencken on food and drink.

I have been traveling and cooking in Europe since July; Paris is the next stop. My books are in the dark, packed away. I wanted to take a few volumes with me when I began this journey, but suitcases fill rapidly, and shoes and knives and clothing are surprisingly heavy once one begins packing for an extended sojourn.

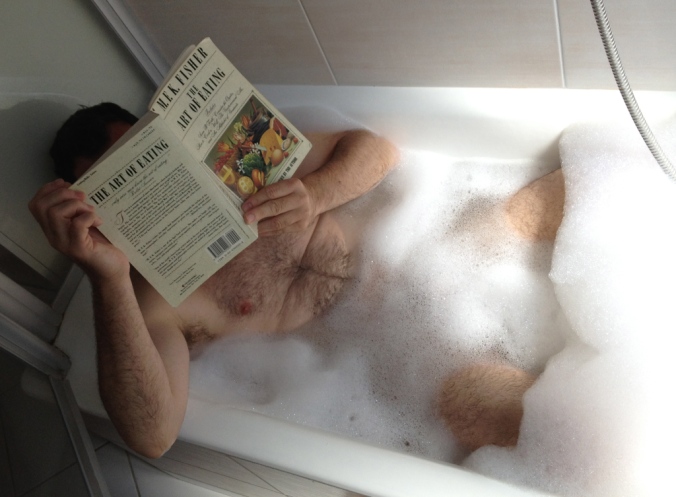

Reading about tête de veau and M.F.K. Fisher’s days and nights in Dijon. (Photograph by Angela Shah)

I have with me one title, The Art of Eating, by M.F.K. Fisher. I recommend that anyone interested in food and life and love – not to mention good writing – get their own copy, or anything by the author. (I am sure many of you already have.) M.F.K. Fisher has nourished me in Germany and Spain and France and Switzerland thus far on this trip, and she’ll continue to do so for a long time. She has shared her thoughts with me about dining alone, which I have been doing a lot of lately, and her love of tête de veau and sweetbreads and the sorrow and frustration resulting from the fact that more people have not discovered the joys inherent in making a meal of these fine staples. (Of the latter, that sorrow and frustration, I feel the same.) The Art of Eating includes a great recipe for tête de veau, and these lines on eating such honest things:

“Why is it worse, in the end, to see an animal’s head cooked and prepared for our pleasure than a thigh or a tail or a rib? If we are going to live on other inhabitants of this world we must not bind ourselves with illogical prejudices, but savor to the fullest the beasts we have killed … People who feel that a lamb’s cheek is gross and vulgar when a chop is not are like the medieval philosophers who argued about such hairsplitting problems as how many angels could dance on the point of a pin. If you have these prejudices, ask yourself if they are not built on what you may have been taught when you were young and unthinking, and then if you can, teach yourself to enjoy some of the parts of an animal that are not commonly prepared.”

I have been reading this volume of collected works (a partial offering of her output) in an effort to get to know Ms. Fisher a little better, and I have. Recently in Switzerland I took the book high up into the hills above Montreux and Vevey, where she once lived and cooked and loved. I was hoping to make my way to what remains of her house in those hills, but instead met some very fine people as I searched for remnants of Ms. Fisher’s life. I’ll tell you about them soon, and of their kindness and hospitality and love for food. And, I have much more to say and write about Mary Frances Kennedy Fisher’s work and life.

In the meantime, read her. And live and love and cook and eat, well.

Recent Comments