Jeremiah Tower’s work on Escoffier is the perfect introduction to the work and life of the famous chef.

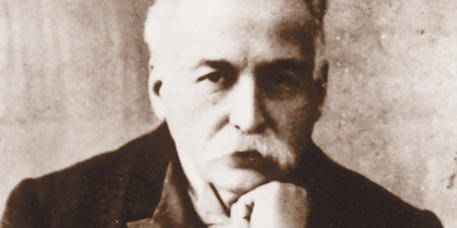

Escoffier. Anyone who loves food, who loves to dine in good restaurants, should know his name. And most definitely, anyone who cooks in a restaurant has a responsibility to be fully aware of his name, and, more importantly, of his profound presence that is all around you as you cook and serve guests. He is one of the luminaries in the chef pantheon.

Now comes an eBook on Escoffier by another famous chef, Jeremiah Tower. Its title is “A Dash of Genius,” and it is a welcome addition to the Escoffier library, especially for readers who don’t know much about the French demigod (whose full name is Georges Auguste Escoffier).

One of the most enjoyable aspects of “A Dash of Genius” is the way Tower tells the reader how Escoffier entered his life, and how the Frenchman’s legacy and lessons have affected his creativity and career. (In addition, Tower’s use of recipes is marvelous, and will make you want to cook.) He begins:

“I have been obsessed with Auguste Escoffier since I was sixteen at King’s College School in London. My drama teacher gave me ‘Ma Cuisine’ for having played Algernon Moncrieff in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Importance of Being Earnest.’ I thought it was a curious choice, but I read it every night under the bed covers with a flashlight after lights out. And was entranced. Later, in Harvard College and cooking for friends, I graduated from ‘Ma Cuisine’ to ‘Le Guide Culinaire.’ I worked through it enough so that when I moved to a little house in Cambridge in my senior year, the first dinner I gave was pure Escoffier.”

Tower goes on to list the menu for that dinner, which took place in 1965, but, as someone who never tires of reading menus, I’ll not spoil your enjoyment. Get this book.

Escoffier, a man of sublime taste and great vision. (Photo courtesy of Ecole Ritz Escoffier)

“A Dash of Genius” begins at the beginning, and tells the story of Escoffier’s birth (1846, near Nice) and early development, establishing the fact that the young man from the south of France had an “iron will” even at an early age. He was working for his uncle, and, according to Tower, this is where Escoffier’s ideas on reforming professional kitchens and, indeed, all aspects of running a restaurant, were born. The formation of kitchen brigades, bringing all the functions of cooking into one unified space (as opposed to cooks working in separate, unconnected rooms), and the improvement of hygienic conditions in kitchens: we owe Escoffier much gratitude for these and many other innovations.

Tower spends a lot of time on Escoffier’s charitable work and other benevolent activities, which were many. For example, Tower recounts the story of two nuns who would daily visit the Savoy, at which Escoffier was chef, on a horse-drawn wagon. The women would go through the restaurant’s garbage looking for used coffee ground, tea leaves, and other items, which they used to feed residents of a rest home. When Escoffier noticed their activities he ordered that all the food thrown away by the restaurant be clean and in good condition, including, writes Tower, quail carcasses, legs and thighs still intact – the restaurant generally used only the breasts of the small birds.

Tower continues: “The day came when there was no horse. No nuns. Escoffier leapt into action and visited the rest home to see the Reverend Mother. All she needed for the horse was five pounds. Escoffier supplied the money and the next day the same two nuns with a new horse pulled up to the Savoy.”

Escoffier continued to help the nuns for more than 20 years. In addition, he was the recipient of, among many other awards and honors, the Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur and the Officier de la Légion d’Honneur. He raised 75,000 francs for the benefit of women and children during World War One, and took on the task of rehiring every cook of his who had gone to war, eventually “implanting over 2,000 French chefs around the world.”

Escoffier founded a magazine, “Le Carnet d’Epicure,” in 1911, and wrote books, the most famous being “Le Guide Culinaire,” which is found in restaurants and home libraries around the world. If you do not own it, please get a copy. It alone would have lit Escoffier’s star in the firmament forever, and its more than 5,000 recipes, not to mention its practical and groundbreaking approach to cooking and producing food for a modern clientele, will be with us until the final pot of stock grows cold.

Jeremiah Tower, whose study of Escoffier is food for the mind and senses. (Photo courtesy of Jeremiah Tower)

Another interesting encounter with Escoffier that Tower tells readers about deals with Chez Panisse, the pioneering restaurant in Berkeley, California, founded by Alice Waters, at which Tower was an instrumental presence. In 1976, Tower was creating menus for a “Week of Escoffier” festival at Chez Panisse, and on this particular night 60 guests were waiting in the dining room for their dinner. Foie gras was on the menu, there because Tower wanted to serve Tournedos Rossini, which he said was a childhood favorite of his. From beyond the grave, Escoffier guided Tower to transform his approach to food and the serving of it to paying guests:

“It was the foie gras that made me rethink what I was doing. In the United States in the early 1970’s it came in cans … After one taste of canned goose liver, I knew I was eating more pig wurst than goose liver, and the canned truffles might as well have been old turnips. Facing a demand to do one more night of Escoffier, I thought, why not his famous Caneton Rouennais en Dodine au Chambertin? Of course, this was as long as I could get the Chambertin. I looked to the local ducks. Reichhardt Duck Farm Sonoma pekins were fine, but trying to convince myself that they could substitute for French canards de Rouen that arrive in the kitchen undressed and still full of blood for the pressed sauces with which they are served was a losing battle. In those days, international ingredients weren’t flown in every day, and frozen foods were a personal anathema. I was faced with using whatever had been produced in the region – and that realization was my “eureka” moment. I looked up from France and saw California.”

Tower goes on to describe how he took Escoffier’s dishes and made them “local,” and anyone who has dined at Chez Panisse (or, by now, most other good restaurants whose chefs and cooks focus as much as possible on seasonal and local ingredients), has benefitted from that “eureka” moment. I recall one lunch at Chez Panisse during which my three dining companions and I were invited into the kitchen upon arrival and given a tour; I was put to work shelling peas, and loved being around the fresh produce grown on farms around the region. (I’ll leave it to others to discuss Tower’s working relationship with Alice Waters.)

Escoffier survived captivity as a prisoner of war in a German camp, opened excellent hotels and restaurants, traveled to the United States on four occasions, and was instrumental in the development and success of countless cooks and chefs. His work pleased royals and commoners alike, and many of his dishes and their offspring are served around the world daily, to the delight of millions. He died in 1935, two weeks after the death of his wife, in Monte Carlo. His guidance, however, is fully with us. Tower’s study deserves a place on shelves devoted to Escoffier, and will, I think, introduce more readers to the work and legacy of the great man.

Recent Comments