It gives me solace that they each lived a long life, these woman whose cooking and writing and spirit gave happiness and nourishment to so many. Pasta, fried chicken livers, a recipe for shrimp and asparagus with sorrel, and eggs Sardou: these things are evocative entry points to, respectively, Romana Raffetto, Mildred Council, Barbara Kafka, and Ella Brennan, four women whose legacies won’t soon fade. Losing them all within the space of a few weeks is a tough blow, but let’s try to celebrate the exuberance and love of food they displayed.

One of my favorite things to do in New York is to walk the streets of the West Village and make the rounds of my shops, including Murray’s, Faicco’s, and Ottomanelli & Sons. For pasta, when I did not want to make my own, or lacked the time to do so, I would stop at Raffetto’s on West Houston Street, pasta whose quality never disappointed. Romana Raffetto, who passed away on May 25, was behind the counter on most days, talking to customers and extolling the virtues of her family’s products, which evolved over time to include all the shapes and types that are now ubiquitous in even the most pedestrian of grocery stores (think pumpkin ravioli and squid-ink tagliatelle). The store, officially known as M. Raffetto & Bros., opened in 1906, and there’s no telling how many meals have been composed with Raffeto’s pastas and sauces since then. I enjoyed talking with Raffetto, and her pride in the store, and what her family had created, was obvious. (If you want to try a few things intriguingly delicious, order the following from Raffetto’s: pink sauce made with cognac, gorgonzola and walnut jumbo ravioli, and black squid Tagliarini all Chitarra. Those are my favorites.)

Stores like Raffetto’s are national treasures, and in many cities are extinct, if they ever existed at all. As I write this, the aromas of that wondrous space in the West Village are all around me, and I know what one of my first stops will be the next time I am in New York. In the meantime, mail order will have to suffice.

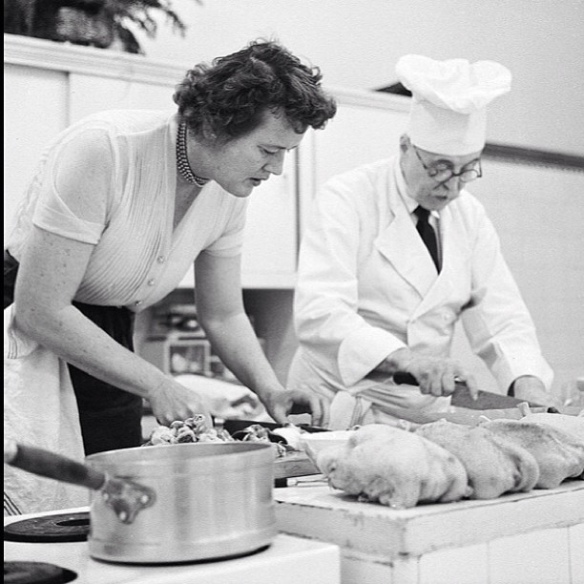

Here’s a look at the place and the people behind it:

Mama Dip. What can you say about Mama Dip, otherwise known as Mildred Council? What about her Community Dinners? Or the courage and bravery she exhibited in choosing to end her marriage after 29 years, in 1976, having endured emotional and physical abuse? “The biggest turning point in my life was when I left my husband,” she told an interviewer in 1994. A cookbook that has so far sold 250,000 copies (“Mama Dip’s Kitchen”)? Fried chicken livers adored by Craig Claiborne (and thousands of other individuals)? How about the fact that she opened her first restaurant in 1976 and had but $40 to make breakfast, and at the end of that first day went home with $135? Her food was honest and filling and delicious and spoke of the lessons she learned cooking for her poor family, which she began to do at the age of 9, when her mother passed away. She was tall — 6 foot 2 — and she was loving and gracious, and Chapel Hill will never be the same.

“I’m not a chef. And I don’t like people to call me a chef because a chef is more like—I call them the artists,” Council told the Southern Foodways Alliance’s Amy C. Evans in a 2007 interview. “They have so much artist in them, artistic, ever what you call it. Artist, I guess, because they can just make things so pretty, you know. And I try to make things good.” Did she ever.

Mildred Council left countless fans and admirers, who will forever miss her cooking. (Image courtesy Mama Dip’s)

Barbara Kafka’s books sold millions of copies, and her advocacy of using a microwave to prepare food — she even used the appliance to deep-fry, alarming many and disgusting others — earned the disdain of many chefs, but the indefatigable author didn’t let the criticism bother her. She pushed on with her testing and writing and consulting, and in 2007 was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award from the James Beard Foundation.

“I do try to write in English, I don’t write ‘kitchen’ and I don’t write French,” Kafka told an interviewer in 2005. “What’s wrong with saying matchsticks instead of julienne?” Clearly, her straightforward — many would say brash — approach spoke to legions of home cooks, who devoured her writing and learned their skills from her books and articles. She supported Citymeals on Wheels early on, spent thousands of hours testing recipes, and maintained a passion for the transformative power of food and cooking. If you like cookbooks with a definitive voice and point of view, Kafka’s are for you. And you know what? Though I do not use the microwave to deep-fry my chicken livers or cook artichokes, I do start my roast chickens at 500 Fahrenheit.

New Orleans is one of my favorite destinations for food and eating. I can still recall the first time my family visited the city; I could not have been more than 10, but the flavor and sights and smells are still vivid in my senses. Strong black coffee, beignets covered in powdered sugar, shrimp and gumbo and everywhere, it seemed, the sounds of jazz.

Ella Brennan and the Crescent City were made for one another, both colorful and romantic and stubborn. “Hurricane” Ella was definitely a force of nature, and her love of restaurants and the people who made them work is worthy of much admiration. Here is all she said at the podium at the 1993 James Beard Awards (Commander’s Palace picked up the Outstanding Service award that year): “I accept this award for every damn captain and waiter in the country.” Classy lady was she.

If you want to read a lively autobiography, get a copy of “Miss Ella of Commander’s Palace: I Don’t Want a Restaurant Where a Jazz Band Can’t Come Marching Through“. Then set aside a part of your evening and watch “Ella Brennan: Commanding the Table.”

The experience will be all the more pleasurable with Miss Ella’s Old Fashioned in hand, a fine drink with which to toast the memories of these four amazing and strong women.

Miss Ella’s Old Fashioned

Ingredients

2 ounces Bourbon

2-3 dashes Peychaud’s bitters

one half-cube sugar

lemon peel for garnish

Fill a rocks glass with ice and a touch of water. In a second rocks glass, muddle the sugar cube with Peychaud’s bitters , then add Bourbon. Swirl the ice in the first glass to chill it, then discard the ice and water. Pour the drink into the now-chilled glass. Run the lemon peel around the rim of the glass, then toss the peel into to the drink for garnish.

Recent Comments